Fact-Finding Hearings in Family Courts

A fact-finding hearing is a standalone hearing in child arrangements proceedings, which takes place to determine whether allegations raised by one person, or two, are true. It is down to the Judge to decide whether the incident(s) did or did not happen. In order to conclude the allegation is true, the Judge must be satisfied ‘on the balance of probabilities’ that the incident did take place. This means that the Judge must be 51% sure that an allegation is true. This is a much lower threshold to meet, compared to a criminal trial. The standard of proof is beyond reasonable doubt, which is why you hear on the TV, Judges asking a Jury, are you sure?

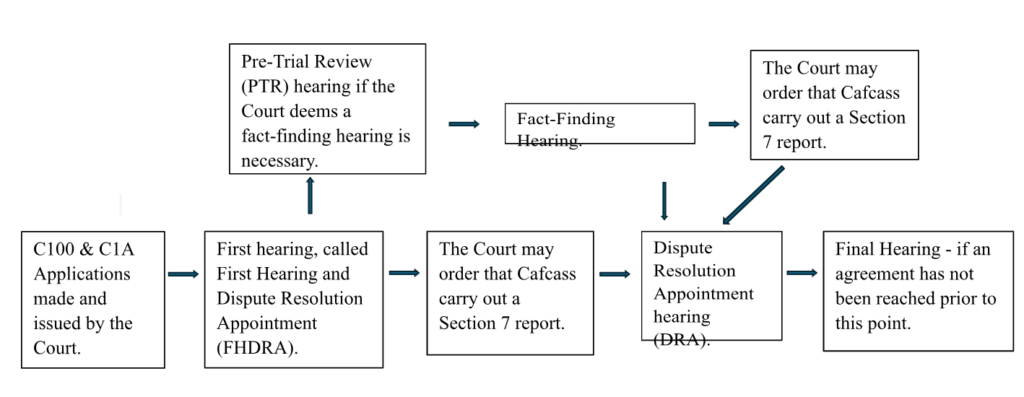

As will be explained below, the child arrangement proceedings will come to a halt, in order to carry out a fact-finding hearing. Once a Judge has decided a fact-finding hearing should take place, other elements, such as contact, are unlikely to progress until the outcome of the fact-finding hearing. Please see the diagram below which explains where a fact-finding hearing comes into play in children’s proceedings.

Children Act Proceedings Timeline

As you can see, a fact-finding hearing takes a separate route of its own and puts a pause in proceedings. Only when the fact-finding hearing has taken place and the allegations have been determined, does the Court timetable resume to its ‘normal’ track. Should a fact-finding hearing not need to take place (because parties have not raised concerns, or the Court has determined it is not necessary), the second hearing will be the Dispute Resolution Appointment. However, the Court is not bound by a strict timetable and may decide later in the proceedings that a fact-finding is necessary or no longer essential to determine the final child arrangements order.

When do I need to have a fact-finding hearing?

Not every allegation of bad behaviour, within family law proceedings, necessitates a fact-finding hearing. When deciding whether to proceed with a fact-finding hearing, the Court must turn to the case of K v K [2022] EWCA Civ 468. In this case, the parents had three children over the course of their twelve-year marriage. The father ultimately filed a C100 application to seek the Court’s intervention as he was no longer having regular contact with the children following the separation. The mother filed a C1A which is a form where a parent can raise welfare concerns about a child, attributable to the other parent, where she made allegations against the father. Consequently, Cafcass became involved and the mother raised allegations of what Cafcass concluded to be rape. Cafcass then invited the Court to consider the need for a fact-finding hearing. When reviewing whether a fact-finding hearing is necessary, the court must ascertain at the earliest opportunity whether domestic abuse is raised as an issue and is likely to be relevant to any decision of the Court relating to the welfare of the child. In very brief summary, the Court on this occasion said that we must consider four factors:

- The nature of the allegations and the extent to which the allegations are likely to be relevant to the making of a child arrangements Order.

- That the purpose of a fact-finding hearing is to allow an assessment of the risk to the child and the impact of any abuse on the child.

- Whether a fact-finding hearing is necessary or whether other evidence suffices.

- Whether a fact-finding hearing is proportionate.

Essentially, what we can conclude from K v K is that the Court is not obliged to hold a fact-finding hearing in every case where domestic abuse is alleged, stating that court proceedings to find out the truth about such issues are difficult, and, whatever the outcome, the hearing will likely have a negative impact on their ongoing relationship and ability to cooperate with each other as parents. Ultimately, the Court’s paramount concern is the child(ren) and how the child(ren) can be successfully cared for by both parents. The Courts understand that trawling though past events may not be beneficial to either parent, particularly if the allegations are historical. Therefore, the Court must determine each case on their own merits and facts. A judge must only conduct a fact-finding hearing where the outcome will make a difference to the final child arrangements Order. In this case, had the father been found to have committed a rape, would this change whatever order for contact would be made?

The much more recent case of A v K [2024] EWHC 1981 considered when a fact-finding hearing will be required. The case puts a positive duty on the Judge to question everyone in court as to why the hearing should happen and how it would affect the welfare of the child(ren) concerned. The court decided that, if the allegations are not relevant to the child’s safety/welfare or the ultimate order the Court will make for the child, then a fact-finding hearing should not take place.

Preparation

When the Court is deciding whether to conduct a fact-finding hearing, they will often ask the person who has raised the allegations to create what is called a Schedule of Allegations, more recently referred to as a Cluster of Allegations or Scott Schedule. The Court can also ask for a witness statement in support of this schedule to provide further information. The schedule of allegations will form the basis of the fact-finding hearing. The parties are encouraged to ‘narrow the issues,’ so that the number of allegations being considered is reduced.

What happens at the hearing?

The hearing can often take more than one day as both parties (the person making the allegation and the person who the allegations have been made against) will be required to give oral evidence; reply to questions in the witness box. This is a very daunting experience. There may be additional witnesses (such as family members etc.), which will make the hearing go on for more than one day. In general, the parents instruct their lawyers to ask questions of themselves, and the witnesses, as well as summarising the case to the Judge after all the evidence has been heard.

The person who has made the allegations will go into the witness box first. Each barrister will ask questions on all the written evidence (statements) before the Court. The same will apply to the other parent.

What if one party wants a fact-finding hearing after the Judge has said no?

Once the matter has been addressed by the Court, the decision is final unless there is new evidence that has come to light which was not before the Court previously. However, the person introducing this new evidence will need to explain why they did not disclose it before the Court previously, but that does not mean that the court will change its previous decision.

What happens after the fact-finding hearing?

The Court timetable resumes to its traditional route, the next hearing being the Dispute Resolution Appointment Hearing. Prior to this hearing date, the fact-finding hearing Judge will likely have ordered that Cafcass become involved in proceedings and carry out what is called a Section 7 report. These reports tend only be necessary if there are concerns about a child’s health and/or welfare. If findings have been found in a fact-finding hearing, it is more likely than not that Cafcass will be directed to carry out a Section 7 report. The report can take between 12 and 16 weeks to complete, but can be longer, depending on the area of the country the child is based. The report must take into account the following factors:

- The ascertainable wishes and feelings of the child(ren) concerned (depending on their age and understanding);

- Their physical, emotional and educational needs;

- Their age, sex, background and any characteristics of theirs which the Court considers relevant;

- Any harm which they have suffered or are at risk of suffering;

- How capable each of the parents, and any other person in relation to whom the Court considers the question to be relevant, is of meeting their needs;

- The range of powers available to the court under this Act in the proceedings in question.

Section 7 of the Children Act 1989 can be accessed at Children Act 1989 (legislation.gov.uk). As a part of the process, the Cafcass officer may speak to the parents, child(ren), wider family members, the school or any health professional in order to obtain any safeguarding information about the child(ren) involved.

If you are considering making an application to Court, regarding your children, or are already in proceedings, please do not hesitate to contact us and speak with a member of our team who will be happy to assist in finding you a way forward.

Can we help you? Please call us on 0333 344 6302 or contact us through our enquiry form. All initial enquiries are free and without obligation.

"*" indicates required fields